Katharine Murphy is political editor of Guardian Australia.

Having spent more than two decades as a member of the Federal Parliamentary Press Gallery, Katharine has earned a reputation as one of the nation’s sharpest political analysts. While based in Canberra, she has worked as a reporter for The Australian Financial Review, The Australian and The Age, and more recently, she has been a part of Guardian Australia‘s team since the website launched in 2013. In addition to her daily reporting and editorial duties, Katharine also writes occasional longform essays for the Melbourne-based literary journal Meanjin.

Having spent more than two decades as a member of the Federal Parliamentary Press Gallery, Katharine has earned a reputation as one of the nation’s sharpest political analysts. While based in Canberra, she has worked as a reporter for The Australian Financial Review, The Australian and The Age, and more recently, she has been a part of Guardian Australia‘s team since the website launched in 2013. In addition to her daily reporting and editorial duties, Katharine also writes occasional longform essays for the Melbourne-based literary journal Meanjin.

In late August, I spoke with Katharine before a live audience at the Canberra Writers Festival, whose theme in 2017 was “power, politics and passion”. Our conversation at the festival touches on Katharine’s approach to political reporting, which requires constant scepticism while avoiding cynicism as much as possible; how her mother’s fiery passion for a Sydney Morning Herald columnist rubbed off on her at a young age; what she has observed about the cultural differences of working for three different media organisations in Fairfax, News Corp and The Guardian; what she has learned about the mechanics and logistics of live blogging political news with little time for coffee or bathroom breaks, and how she came to write an intimate and moving essay about the joys and sorrows of raising her daughter.

Katharine Murphy has worked in Canberra’s parliamentary gallery for more than 20 years, starting at The Australian Financial Review, where she was Canberra chief of staff from 2001 to 2004. In 2004, Katharine moved to The Australian as a specialist writer until 2006, when she became national affairs correspondent at The Age. In 2008, she won the Paul Lyneham award for excellence in press gallery journalism, and has been a Walkley Award finalist twice: for digital journalism for her pioneering live politics blog, and for political commentary. She is a regular panelist on the ABC’s Insiders program, on ABC24’s The Drum, and Sky News Agenda. Katharine is Guardian Australia‘s political editor, and has worked there since the site’s inception in 2013. She is also a regular essayist for the quaterly literary journal Meanjin.

Katharine Murphy on Twitter: @Murpharoo

Special thanks to the team behind the 2017 Canberra Writers Festival for hosting this conversation, and thanks to Bevan Noble at B Natural Productions for recording the audio.

Direct download | iTunes | Stitcher | Libsyn | YouTube

Timeline:

2.30 Katharine has an essay in the winter 2017 issue of Meanjin named ‘The Political Life is No Life At All‘, in which she wrote that a toxic work environment threatens the health of Australian democracy

3.30 “As a long-term political journalist and practitioner, I honestly do not believe at any time that the political class in Australia went to bed one night, woke up the next morning with a burning aspiration to screw things up. I really don’t think that happened”

5.00 Katharine found it hard to get politicians to talk on the record for this story, as they “fear being spurned by their peers; they fear being judged by the media and the public if they present their own human face to the community. They’re quite scared about doing that, and the consequences of doing that”

6.00 “The objective of this piece was to get them to narrate their own story; rather than me interposing myself significantly in the essay, I wanted them to tell their own story, and it’s conducted in the sort of style of ‘exit interviews'”

7.00 Katharine already knew her interviewees for the essay well, so “I suppose they had a basic level of trust; they knew I wasn’t a cowboy. But none of them were very happy about doing it”

8.00 While interviewing former politicians and staffers for her essay, Katharine was conscious of the need to project that it was a safe space to have a difficult conversation, where she told them: “‘I get where you’re coming from, and I want to tell this story in a way where the Australian public can understand it. This will be okay.’ I’m not generally reassuring in interviews with politicians; it’s not generally my style”

11.00 “It’s a really tough business. Again, I didn’t write the piece as some sort of great, big public apologia for politics; I didn’t write the piece to try and get everybody having mass waves of sympathy for parliamentarians”

14.00 “The purpose of the piece wasn’t for the pity party of ‘woe is politics’; this has a practical implication for all of us. If democracy gets to a point where the lifestyle is so punishing – the terrain is so punishing – that it’s no longer a safe space for a human being to occupy, then that has implications for the quality of representation: we will only get a particular type of personality who wants to get into politics”

15.30 Since its publication in mid 2017, Katharine saw a “massive” response to the article, particularly from politicians and political staffers; it was so popular that it broke the Meanjin web server, and they had to buy additional bandwidth to cope with the traffic it was bringing to the site

16.30 “I’ve had the most amazing conversations with people since that essay was published […] I’ve heard the most amazing stories from people about what their perception is about the culture inside their party rooms, and what political staff are doing to sustain themselves in these jobs”

18.30 Katharine finds that if she’s not writing quickly, there’s a problem, generally with the structure or the thesis of a particular piece. With her Meanjin essay, “as I spoke to the three protagonists, I saw this tragedy in three acts in my head. That’s how the piece spoke to me, as a conceptual frame”

19.30 “In these longform things, I tend to get down a draft fairly quickly, but the process of refinement takes the time, where you’re just literally twiddling buttons; you’re turning volume down, turning a little bit of volume down, and I have trusted people who I often seek guidance from”

20.30 When writing long articles, Katharine shares early drafts with a small group of people whose opinions she trusts and values, including her husband, Mark Davis, who is “a marvellous in-house support for my work, and he is very tough on my work. He doesn’t spare me, which I don’t always appreciate, but I always benefit from”

22.30 Her editor at Meanjin, Jonathan Green, is “a great friend and a great support”; Michael Gordon “has been quite influential in my work and style”, and Gabrielle Chan “is a wonderful, wonderful writer, and is always helpful if I really need her to read something, or give me feedback”

23.00 Fellow political commentator Michelle Grattan is a member of Katharine’s “psychic gallery brains trust”; the two of them recently found that they wrote similar columns at the same time, which was “a weird crossover moment”

25.00 Katharine says that she is the least cynical person she knows, and it’s an active choice she makes: “You can sink into that sinkhole. The most essential quality about political reporting is that one must be sceptical all the time […] But if you’re cynical, you’ve kind of lost it […] and the audience doesn’t benefit from your cynicism”

26.00 “I find when I’m hitting particularly nihilistic territory, which I have been lately […] I step back and change my point of view, and look for something inside the process that is working, still. Or find a group of people who are in politics for the right reason, and try and tell their story, which is not really being told in the great big narration of dysfunction”

27.30 In her childhood during the 1980s, Katharine’s mother had a “fiery passion” for The Sydney Morning Herald columnist Alan Ramsey: “From a very early age, my mum would put me on the back porch in front of Alan Ramsey’s column and insist that I read it, top to toe”

29.00 “I was one of those dreadful kids who always kept a diary; who had the most florid, horrendous stories in the diary; who was always writing; who was always looking for means of creative expression”

29.30 “I always thought in the back of my mind, ”It’d be great if you could somehow be a political journalist in Canberra’, but I didn’t know really how one did that, so I went to university and did an arts degree “, then came to Canberra in 1991 and joined the public service, before befriending some press gallery journalists

30.30 An early career influence was the journalist and editor Tom Burton, who hired Katharine on The Australian Financial Review, where she started on the industrial relations round in 1996

32.30 “I was a completely hopeless journalist in terms of tradecraft; but I knew the area, I knew people I could go to for background information, and that was enormously helpful to me in that reporting period”

33.30 From there, Katharine moved to The Australian for a change, then Michelle Grattan brought her back to report on politics for The Age, before later joining Guardian Australia when it launched in 2013

34.00 Katharine says that Fairfax, News Corp and The Guardian have “all got different cultures, and different obsessions, preoccupations, things that are important to them […] there’s a certain similarity between the Fairfax culture and The Guardian culture, but it’s a bit different. And News is its very own thing”

34.30 Katharine says that her employer hasn’t affected how she has reported on politics throughout her career, as “I’m kind of tough to budge; I’m not very malleable”

36.00 “At The Guardian, we are very, very interested in the environment; we are very, very interested in the fate of people less well off than ourselves; we are very, very interested in whether the people we are currently detaining indefinitely in offshore detention are living or dying under our care”

37.00 What makes a good editor? “Editors that are reassuring to journalists are editors who stand in the trench with the troops, and are completely part of the journalistic mission”

38.00 Katharine also lauds the efforts of “backbenchers”, or copy editors who help with tweaks before publication: “People like Patrick Smithers, a long-time night editor for The Age in Melbourne, is one of the most brilliant backbench operators I’ve ever had the pleasure of working with. That guy was unflappable under pressure”

41.00 Katharine tries to bring that idea of being in the trenches with the troops to her role as political editor at Guardian Australia: “I’ve worked for a lot of political editors in my time […] I’ve always benefited from people who are hands-on, and who have worked with my intensively at times, when I’ve needed it”

42.30 On making mistakes in journalism: “You need to correct those mistakes quickly and honestly and transparently, and move on”. Katharine recalls making a mistake about waterline data while reporting on industrial relations for The Australian Financial Review

44.30 When it comes to cultivating sources as a political reporter, Katharine says it’s important to be honest and transparent: “The best thing you can do is be trusted, so that people know that they can tell you something approximating the truth, and that you’ll report it fairly, or on some occasions, that you won’t report it, because you’ve undertaken not to”

45.30 Katharine thinks young reporters can sometimes over-complicate these relationships by wanting people to like them: “It’s just not important. People have to get to know one another on their own terms, and reach a basic operating point of trust”

46.00 “The best thing about being a long-term political reporter is that, if you stick at this for 21 years, you learn not to be afraid. You’re dealing with very powerful people; with the most powerful people in the country. That can be, when you first enter the field, quite intimidating. But the longer you do this, you learn that you will probably outlast everyone who is sitting before you in the parliament, and all of their staff, and all of their underlings”

47.00 “I think the longer you do it, the less afraid you get. And the less afraid you are, the more honest you will be as a reporter. That’s the benefit of longevity in Canberra”

48.0 Katharine first began live blogging at The Age, then brought the concept across to Guardian Australia when she started there, having been an avid reader of Andrew Sparrow’s live blog on UK politics for The Guardian

50.30 “It’s quite a thing, live blogging: it retools you as a journalist, in all kinds of ways, and you come out the other side like you’ve had the most massive grease and oil change you’ve ever had in your life”

51.00 Katharine wrote about live blogging for a 2013 Meanjin essay, ‘This Connected Life‘, where she wrote that “bathroom and coffee logistics became a significant preoccupation on a live blogging day”, which demands updates every 10 minutes

52.30 In that 2013 essay, Katharine reflected on the 24/7 media cycle, which has only become more intense in the four years since: “Journalism’s gone through this major technological disruption in my reporting lifetime. The first ten years, I was a newspaper person; the next ten years I was a digital person, and that’s just because of the intrusion of the internet”

54.00 When she wrote that essay in 2013, Katharine was more optimistic about the transformative effects of technology on journalism than she is now: “We’ve had no privacy to make this transition. We’ve had to do it in full public view, basically”

58.00 “The art of ‘live’, for those of us who practice it – and who care deeply about our profession, and who don’t want to fail our audiences – what we’re trying to do in this mode is give you new, important, quality. That’s a very, very, very tough benchmark to set yourself”

59.00 How Katharine manages to switch off from her role in journalism: “In my life, I am totally ‘on’, and I am totally ‘off’. It’s the only way to survive”

60.30 In 2016, Katharine wrote a Meanjin essay called ‘The Hair Apparent‘, which was about her 17 year-old daughter leaving home and going off to live an independent life as a student in Sydney

61.30 “It hit me hard. It hit me like a ton of bricks. I felt as though I needed to put some structure around it, in a writerly sense, because that’s how I cope with pretty much everything: writing about it, writing about chaos of any type”

62.30 “It celebrates her independence, and my very curmudgeonly attitude to it. It was good for both of us; my daughter and I both felt good about that piece, and it was a nice farewell”

64.00 Before she wrote it, Katharine asked her daughter’s permission. “She looked a bit trepidatious, and said, ‘Let’s see how we go with that’. I wrote it and gave it to her, full of anxiety […] I took it rather nervously into the bedroom, and handed it to her. She shut the door […] and then she came out and said, ‘Mum, this is amazing. You’ve gotta do it'”

66.30 Katharine’s daughter later had the strange experience of attending a social gathering in Canberra, and overhearing two adults talking about the piece: “She came home quite delighted, and retold this story to me, that she was the silent figure in the middle of this party, where nobody knew”

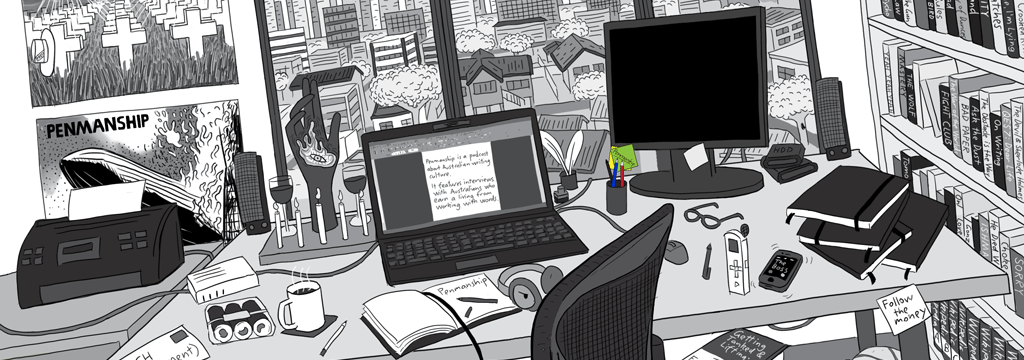

Photographs

The below three photographs from this interview were taken by Stuart McMillen.